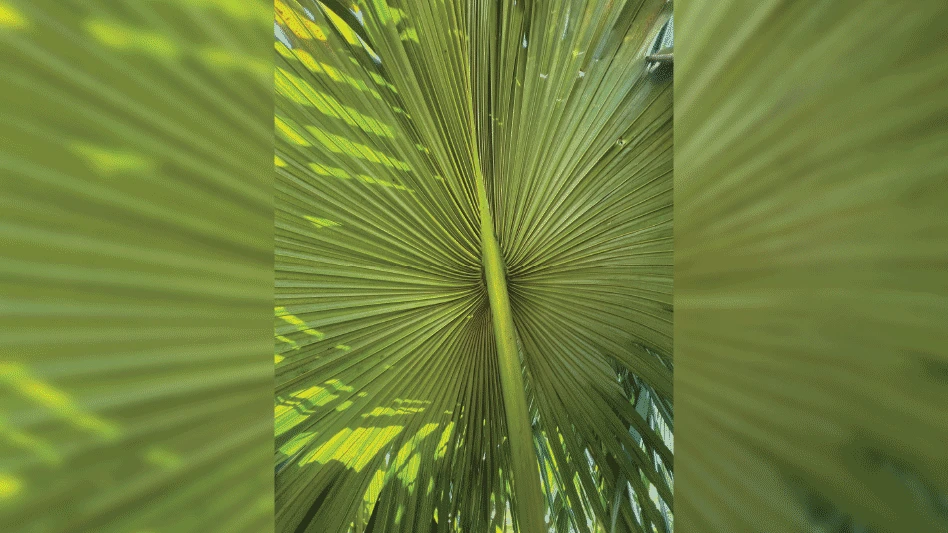

Green infrastructure is a design strategy based on improving water quality and adding ecological functionality to new and existing development through the use of plant material. Communities around the world are conserving, restoring and enhancing natural areas by incorporating trees, rain gardens and vegetated roofs that mimic natural systems and achieve benefits including improved public health, economic development and reduced flood risk.

This technique relies on the use of soil and plants to manage storm water and create low-maintenance, healthy ecological systems. These designs can be used to reduce the need for expensive gray infrastructure, such as storm water drains, pipes, storage facilities and treatment systems. Considered a “triple bottom line effect,” green infrastructure saves municipalities and tax payers’ money, while improving the environment and adding to social appeal. Consider the carbon dioxide that is absorbed improving air quality, the increased property values as a result of the plantings and all of the new local green jobs installing, maintaining and growing the plants for these public spaces. Additionally, these planting systems create habitat and food for wildlife while protecting water quality by controlling soil erosion.

Designed to capture storm water, green infrastructure improves water quality by filtering polluted runoff before it reaches waterways. Plants and soils soak up, store, and use the rainwater. These designs help recharge groundwater systems and increase flows to streams, rivers, lakes and reservoirs. Added values include the minimal required maintenance and low irrigation needs once a site is established.

Big business

There is great diversity in the use and function of green infrastructure. Rain gardens, green roofs and walls, bridges, greenways, urban canopies and green parking lots are just a few examples of high impact designs meant to utilize natural resources and create quality environments.

“Everyone should agree upon an expanded definition of what green infrastructure means. We’re well beyond the world of rudimentary detention basins and bioswales and sedum green roofs,” says Patrick Cullina, principle of Patrick Cullina Horticultural Design + Consulting in New York City.

“A vastly more diverse realm of landscape systems are integral components in large, sophisticated and influential municipal projects.”

Examples of green infrastructure developments are being constructed across the U.S., and Cullina has lent his design acumen and horticultural expertise on many.

“The High Line is a bridge, as is Bethlehem Steel’s Hoover Mason Trestle. Hudson Yards and Manhattan West are platforms over active rail lines; Boston’s Rose F. Kennedy Greenway is the roof of a vehicular tunnel and nearby Pier 4 project is just that,” Cullina explains.

The city of Philadelphia is utilizing these techniques as a financial and logistical solution to replace the existing gray infrastructure that is in rapid decay. It was estimated to cost $6 billion to restore the city’s storm water system. Developers, ecologists and planners generated a cost effective green infrastructure plan. During the next 25 years, Philly will spend $1.2 billion to overhaul and replace storm water systems, and $800 million will be used for green infrastructure projects utilizing plants.

This ambitious project, referred to as “greened acres,” will convert 9,600 acres, or 34 percent of the city’s impervious surface (15 square miles) to permeable ground. The equation was derived as one greened acre is equivalent to one inch of managed storm water from one acre of impervious drainage area resulting in 27,158 gallons of storm water.

Plant diversity

It is important to recognize that the green infrastructure market is driven by ecological regulations, meaning the plants must perform at a certain level within the system. The entire approach is based on scientific studies and the reports written in justification are cited with scientific literature. The use of genetically diverse native plants is fundamental as those species have evolved in an area and are therefore predisposed to performing well in that same eco-region. Bio-diversity is the key component for meeting green infrastructure planting requirements. Seed grown selections of locally native plants support the diversity needed to establish a well balanced eco-system.

There is a high demand for regionally native trees, shrubs, grasses and perennials in green infrastructure design. With a greater resistance to insects and disease, locally native plants preserve a sense of place through natural heritage while fostering a well balanced, bio-diverse ecosystem.

Plants selected for green infrastructure plans will vary based upon region and function; specimens cited for green roofs will be dramatically different from those used in rain gardens or urban canopies. This diverse market continues to expand and evolve as new development regulations have increased demand significantly. Availability remains the largest obstacle in this otherwise thoughtful and environmentally responsible utilization of horticulture. Sourcing seed grown, regionally native plant material can be cumbersome. Deviations from original planting plans compromise the integrity of the ecology and frustrate developers, designers and installers.

“I know from trying to source plants for my projects there remains a considerable market opportunity for nurseries to grow more of the many plants that can thrive in these various applications,” Cullina says. “Some plants that I find quite useful — the straight species form of Chamaecyparis thyoides for example — are nearly impossible to find.”

As this demand increases, nurseries such as Native Roots in Twin Falls, Idaho, grow to meet the need. Native Roots is a liner producer of genetically diverse western region native plants.

“This is an opportunity to present plants that go beyond beautiful — ones offering far reaching and practical impacts benefitting Americans and our landscape for generations to come,” says Steven Paulsen, owner of Native Roots.

The Native Roots line of plants “expands the potential uses of natives in traditional settings” says Paulsen. These selections have become suitable substitutes for traditional plants, “effectively allowing for a win-win with habitat connectivity and function as well as achieving the goals set forth by a landscape architect. The native plants available in the market now allow for much more refined application.”

The nursery’s role

Many nurseries are growing plants appropriate for green infrastructure projects. Growers should find out what projects are being planned regionally, learn more about the environment those projects present and identify the plants in production that fit those conditions.

“As the GI [green infrastructure] market builds, there will be demand for a broader palette of plants. If you can work appropriate plants into your new production plans, you’ll be ready for it,” says Shannon Currey, marketing director at Hoffman Nursery in Rougemont, N.C. “We’ve been reviewing our offerings and expanding to include more native sedges, for example, because they work really well for many GI projects. Also, we’re adding more cultivars, especially those of native species, to have a wider variety for designers to choose from. Until the market is more mature, it may be difficult to gauge appropriate inventory. That’s where tapping into upcoming projects can help a lot.”

Nursery sales and marketing staff can begin to break down the barriers by communicating with designers working on GI projects.

“Nurseries need to do their part in responding to the potential market but they can’t do it without the designers who can help to build that market with a more considered and nuanced approach to design,” says Cullina.

Currey also suggests that growers connect with the landscape architecture and engineering firms, municipalities, regional authorities and non-profits that are planning green infrastructure projects.

“We’ve been using connections to find out what’s happening around us. In some cases, we’ve been able to be a part of the planning process. That allows us to know when plants are needed and have them ready and to custom grow plants that we might not otherwise include in regular production. That’s a way to bridge that gap between supply and demand until the market becomes more stable,” Currey says.

Follow up with contractors to get feedback on how plants are performing.

“Direct experience from existing projects helps us get a read on whether a plant should be marketed for GI,” she says.

Green infrastructure awareness and education are essential for moving the nursery industry forward in this market. Embrace the opportunities ecological design offers and promote horticulture as a solution for community health and wellness for generations to come.

Brie Arthur is a plant propagator, landscape designer and green-industry communicator based in Raleigh, N.C.

Get curated news on YOUR industry.

Enter your email to receive our newsletters.

Explore the March 2016 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Nursery Management

- NewGen Boxwood added to Proven Winners ColorChoice line

- Terra Nova releases new echinacea variety, 'Fringe Festival'

- American Horticultural Society names winners of 2025 AHS Book Awards

- Nufarm announces unified brand

- American Horticultural Society announces winners of 2025 Great American Gardeners Awards

- Shifting the urban environment

- The Growth Industry Episode 3: Across the Pond with Neville Stein

- What's in a name?