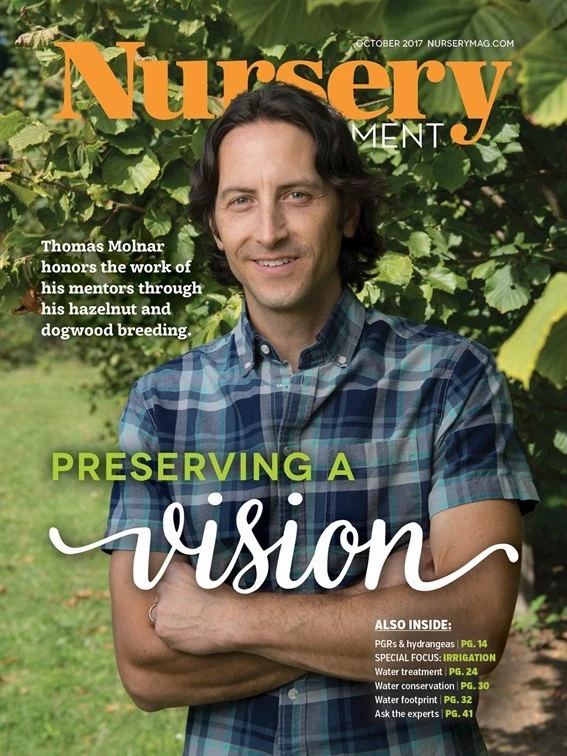

As a young college student with a passion for genetics and applied research, Molnar discovered plant science through an introductory plant biology course and subsequently secured a job in a plant research lab at Rutgers working under the direction of Reed Funk during the summer after his freshman year.

Funk was a highly successful plant breeder and one of the first to develop cool-season

“[Dr. Funk] really had a serious impact on me in many ways and of

From turf to trees

After a few years of breeding turf grasses, Molnar shifted his efforts entirely to breeding trees, under the direction of Funk. The 18-year-old student worked six to seven days a week to keep up with his 70-year-old cohort who never seemed to tire of breeding trees.

Funk introduced Molnar to an ornamental tree breeder at Rutgers named Elwin Orton. Molnar could not have imagined a better pair of mentors. He truly was in the right place at the right time to launch his own career in plant breeding.

“I realized the amazing things Dr. Orton had accomplished during his career, and how hard he worked to get where he was. For example, his notebooks, which we still have in the lab today, are some of the most meticulous and detailed hand-written notes that I have ever seen, and they represent thousands of hours of work and immeasurable dedication,” Molnar says.

Once it was decided that Molnar would take on Orton’s work after he retired, Orton began to share his most carefully guarded secrets he had developed through decades of meticulous ornamental tree breeding work. Details on how he made his crosses, stored pollen, best plants to use in crosses and more, were all recorded in his notebooks. Molnar became one of Orton’s few trusted confidants while also continuing his work on nut trees, which had been started by Funk, his other mentor.

“The exposure to both Dr. Funk and Dr. Orton’s approaches to breeding very strongly shaped the plant breeder I am today. Both accomplished their goals in different ways, but both were very successful. One thing they had in common was both spent nearly all of their time out in the field or greenhouse with their plants. They were not inside working in the

Molnar, too, developed a keen eye for new traits in ornamental and nut tree breeding.

“I learned to look very critically at plants for their ornamental attributes such as their leaf and flower color, shape, texture, and general appeal to the eye,” he adds.

Breeding Corylus for disease resistance

In Molnar’s current ornamental hazelnut breeding program, his team has been using the red-leaf gene from a European hazelnut and crossing it with the native Eastern U.S. hazelnut, Corylus americana. They are selecting seedlings that exhibit the dark purple foliage color of the European

The resulting seedlings include a bonus trait of bearing nut clusters with frilly, dark red or purple husks. The nuts are small but very ornamental and good to eat. The goal of this breeding program is to eventually develop disease-resistant hazelnuts of all forms including weeping trees, contorted trees, trees with purple leaves, yellow leaves, highly dissected leaves and tall street trees. Their first ornamental hazelnut introductions are due to be released soon.

Molnar is also very close to introducing the first nut-producing hazelnut trees from their breeding program. Nut-producing hazelnut trees are currently grown only in a small range in Oregon’s Willamette Valley due to their high susceptibility to Eastern Filbert Blight in other parts of the country. Molnar described how supply can’t keep up with the growing demand and says that most of the hazelnuts sold in stores today are grown outside of the U.S., often in Turkey.

Hazelnuts are a low-input, high-value crop. Through the breeding of

“The idea of bringing a new crop to our region that demands a lot

He is looking for support from commercial tree growers who could provide his trees to nut tree farms. Molnar estimates there are more than 30,000 acres available across New Jersey and southward on which to grow his new disease-resistant hazelnut trees.

Training the next generation of breeders

In his role as

Over the course of his career, Molnar has seen a shift toward using molecular biology to enhance breeding efforts.

“It is no longer very expensive to sequence a genome and to use all of the great genomic tools that come along with these sequencing technologies once reserved for medicine,” he says.

The plant scientist in him is excited for what tools lie in the near future for himself and his students.

Whether he realizes it or not, Molnar has become the mentor he once had in Funk and Orton. His students are incredibly fortunate to have the guidance of someone so passionate about his work, and in the end, we will all have Molnar to thank as we roast fresh hazelnuts over our next fall campfire.

Explore the October 2017 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Nursery Management

- The Growth Industry Episode 3: Across the Pond with Neville Stein

- What's in a name?

- How impending tariffs and USDA layoffs impact the horticulture industry

- Shifting the urban environment

- These companies are utilizing plastic alternatives to reduce horticultural waste

- How to create a sustainable plant nursery

- Lamiastrum galeobdolon ‘Herman’s Pride’

- One of rarest plants on earth: Tahina spectabilis