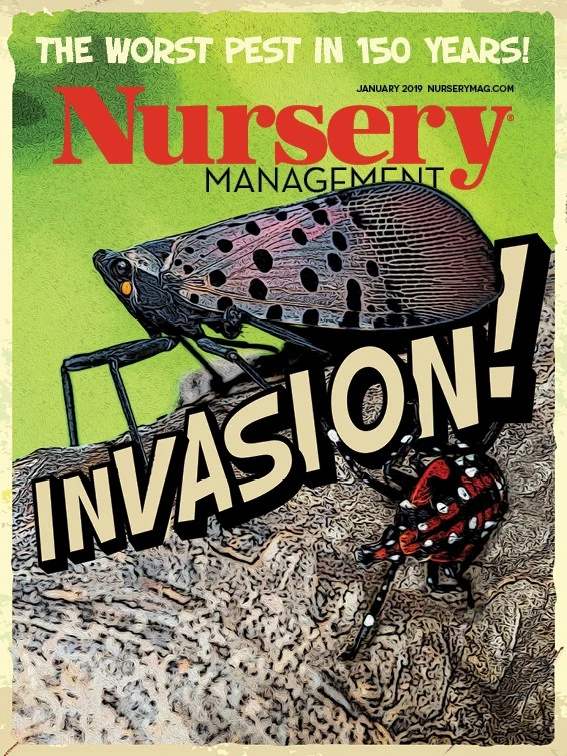

The spotted lanternflies are coming. These sneaky invaders are a menace to more than 70 types of plants.

Viral videos have raced across social media, showing hordes of lanternflies covering buildings and tree trunks. They hop from plant to plant, sucking sap from branches, stems and trunks.

The epicenter of the lanternfly invasion is Berks County, Pa., where the insect was first discovered in the U.S. in 2014. Native to Southeast Asia, the spotted lanternfly has captured attention for its ability to spread quickly. In the four years since its discovery, the insect has spread from one county to 13. It also has been spotted in Maryland, Delaware, New York, New Jersey and Virginia. This pest not only threatens nursery crops – it attacks several species of hardwood trees – it also poses serious problems for high-value crops such as wine grapes and hops.

“I think we’ll really start to see this pest explode in 2019,” says Jill Calabro, science and research programs director for AmericanHort.

In June, the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture suggested the spotted lanternfly might cause $18 billion in damage statewide. In August, Rick Roush, dean of Penn State University’s the College of Agricultural Sciences, called it “potentially the worst introduced insect pest since the arrival of the gypsy moth nearly 150 years ago.”

The horticulture industry has been watching warily, waiting to see if these hoppers will hop onto their radar.

“They know, but they’re not sure if they need to be concerned just yet,” Calabro says. “I think people are kind of waiting to see if this will be a real concern for our nursery industry and for the landscape managers. Chances are, some folks will definitely be impacted.”

Spot the invader

The spotted lanternfly feeds on a wide range of fruit, ornamental, and hardwood trees, including grapes, apples, walnut and oak. The pest damages plants as it sucks sap from branches, stems, and tree trunks, causing dieback. The repeated feedings leave the tree bark with dark scars.

“We’ve definitely seen ornamental trees, walnut, maple, birch and some of the oaks, with thousands of insects feeding on sap, on the trunks,” says Emelie Swackhamer, a horticulture extension educator at Penn State Extension. “And that has distressed those trees.”

Adult spotted lanternflies are approximately 1 inch long and one-half inch wide. They are easily recognized by their large, visually striking wings. Their forewings are light brown with black spots at the front and a speckled band at the rear. Their hind wings are scarlet with black spots at the front and white and black bars at the rear. Their abdomen is yellow with black bars. Young nymphs appear black with white spots and develop red patches before becoming adults. Egg masses are yellowish-brown, covered with a gray, waxy coating prior to hatching.

While feeding, spotted lanternfly excretes a sticky fluid, which promotes mold growth and further weakens plants. As a plant hopper, it can move short distances on its own, but its spread has been aided by people who accidentally move infested material or items containing egg masses.

The spotted lanternfly is an excellent hitchhiker. It will lay its eggs on almost any flat surfaces, which facilitates its creep across county and state lines. All it would take is one egg mass on a railway car or shipping truck, and the East coast’s problem pest becomes a cross-country sensation.

The pest seems to be more of a threat to travel on inorganic material like metal than trees and shrubs.

“It doesn’t seem to be moving around so much on infested plant material, which I think is a good thing for our industry,” Calabro says. “It’s more of a hitchhiker on just normal outdoor items, which is even more scary because it’s out of our industry’s control. Our industry is typically very good at being proactive at controlling pests, mitigating compliance agreements and in setting up systems, guidelines and best management practices. And this is just a pest that, in my opinion, will escape that.”

Containing the horde

Several states have established quarantines to restrict the pest’s movement. In September, USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service and its state partners conducted lanternfly detection surveys in Delaware, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia and West Virginia to monitor existing pest populations and detect new outbreaks outside known infested areas. State ag department staff and local extension specialists are enlisting the help of citizen volunteers, area master gardeners and anyone willing and able to lend a hand.

“Any of the adjacent states and beyond, anyone on the East Coast should be concerned at this point,” Calabro says. “And frankly, the Midwest should start being concerned since Pennsylvania is a state with a population.”

The Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture has required all businesses and organizations moving vehicles, equipment or goods in or out of the quarantine zone to have a special permit.

If your company needs a permit, an employee must complete a free online course from Penn State Extension and PDA. The course uses informative videos to teach the company representative how to identify the lanternfly, its life cycle, what it likes to eat, where it likes to lay its eggs, how to destroy it and more. Once completed, the business will receive a tag for its vehicles to show that it has the SLF permit from the PDA.

Swackhamer is one of the spotted lanternfly experts that teaches the online course. She says the nurseries that have contacted her want to know about the pest management side of spotted lanternfly prevention and how it will affect their profit margins. But they’re also concerned about the quarantine regulations. The 13 counties in Pennsylvania that are part of the state’s quarantine zone are in the southeast corner of the state, which means many of the nurseries located there ship out of state.

“There’s a lot of nursery production in this area and to ship the stock it needs to be inspected,” she says. “The nurseries need to be operating under all of the regulations of the quarantine order. We’re seeing that the surrounding states, for the most part, are accepting the Pennsylvania compliance documentation from our nurseries. But it’s another step.”

Starting May 1, the PDA’s Bureau of Plant Industry will begin performing inspections and verification checks to confirm that businesses have permits. Failure to comply could result in possible penalties and fines.

New York and New Jersey have also issued their own quarantines.

Last January, spotted lanternfly was found in a 1-square-mile area in the city of Winchester, Va. An inspector for the Virginia Department of Agriculture found it at a business that had Ailanthus altissima (tree of heaven) on the border of its property. Over the course of a year, lanternflies have spread to a 6-square-mile area on the city’s outskirts.

Virginia Tech University is also developing a module to train people on the insect and a compliance agreement that states they know how to look for it and how to inspect their cargo.

of Agriculture

Hope for control

Many eradication efforts start with the insect’s preferred host, the invasive tree of heaven.

“It’s like a gateway drug for spotted lanternfly,” says Eric Day, manager of the Virginia Tech Insect Identification Lab, which is helping monitor the insect’s geographic reach.

Virginia’s Department of Agriculture started a program to identify properties with tree of heaven playing host to spotted lanternfly, initiate contact with the landowners and begin a treatment program. Day says nearly all the properties in Winchester have been treated.

USDA APHIS researchers are working on potential biocontrol solutions, including an egg parasitoid wasp. Spotted lanternfly overwinters in egg cases on the bark of the host tree. A wasp could parasitize those eggs before they hatch.

“As with any invasive, first you’re hit with reality of its arrival, then you research where it came from, then it involves foreign exploration to go back and see what controls it in its native range,” Day says. “That’s the stage right now.”

_fmt.png)

It does take time for biocontrol solutions to develop. The research team has to follow a slow, careful process to ensure a potential lanternfly biocontrol agent isn’t going to become a problem pest itself.

“We are trying to stay optimistic about control,” Day says. “Eventually the right number of natural enemies are brought over, and we can see some control down the road. But unfortunately, we will probably see this insect run amok for a while and cause some problems before we see some good biological control.”

There are some conventional chemistry control measures for the nymphs and the adults. Calabro says the neonicotinoid class of insecticides, particularly dinotefuran, work effectively and quickly as a rescue treatment. Growers that have stopped using neonics can use bifenthrin as an alternative, but it won’t work as well due to its non-systemic nature.

A second method of control is tree banding – outfitting a tree with a band of sticky tape that contains and kills young spotted lanternflies. Penn State Extension’s recommended treatment for reducing the population includes installing sticky bands from mid-May to the end of August to trap lanternfly nymphs.

Researchers have also created “trap trees” by eliminating all but one or two trees of heaven and treating the remaining trees with insecticide.

In February, Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue announced $17.5 million in emergency funding to stop the spread of the spotted lanternfly in southeastern Pennsylvania. More than 30 research projects are focused on understanding this invader, with more to come in 2019.

For more: https://extension.psu.edu/spotted-lanternfly; www.aphis.usda.gov/hungrypests/slf

Explore the January 2019 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Nursery Management

- Plant breeding as an art

- Society of American Florists accepting entries for 2025 Marketer of the Year Contest

- Sustainabloom launches Wholesale Nickel Program to support floriculture sustainability

- American Horticultural Society welcomes five new board members

- Get to know Christopher Brown Jr. of Lancaster Farms

- American Floral Endowment establishes Demaree Family Floriculture Advancement Fund

- The Growth Industry Episode 3: Across the Pond with Neville Stein

- The Growth Industry Episode 2: Emily Showalter on how Willoway Nurseries transformed its business